This blog post is about Muslim Americans serving in American politics including the U.S. Government. There are two Muslims in the House of Representatives, and interestingly both of them are converts. There is also a Somali women who is serving as an elected official in the Minnesota legislature. This blog also discusses how some people believe President Obama is a secretly practicing Muslim, and how this effected his campaign. This blog post is another example of how sociological theories actually impact people, especially in light of the recent election.

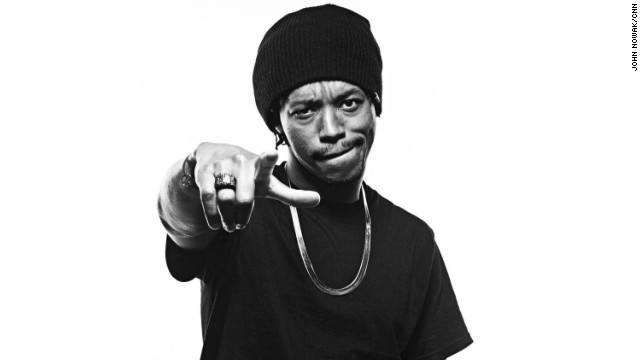

Andre Carson: Muslim American in the House of Representatives

Born and raised in Indianapolis, Indiana, Andre Carson was raised as a Baptist. However, later in his teen years he converted to Islam after witnessing Muslims “pushing back crime” in his neighborhood. He later decided to work in the anti-terrorism unit in the Indiana Department of Homeland Security. Carson was inspired to do so because he was arrested at age 17 after police officers tried to go into a mosque without probable cause. Carson now holds a Bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice Management from Concordia University-Wisconsin and a Master’s in Business Management from Indiana Wesleyan University (Carson 2016). He worked full-time in law enforcement and served on the Indianapolis City-County Council before taking office.

Andre Carson is now the U.S. Representative for Indiana’s 7th congressional district. Carson was elected in 2008. He is also a member of the Democratic Party. “Carson is one of only two Muslims serving in Congress. The other is Rep. Keith Ellison” (Garsd 2015). Carson actually won and took over the seat that was originally held by his grandmother Julia Carson. During this campaign Carson criticized Marvin Scott (Republican opponent) for attacking Carson and his religion. He faced the same discrimination of his religion in 2010 when he reclaimed his seat in congress. (King 2010)

Carson has been put on record in a negative light due to some of his comments. Carson said, “The Tea Party is stopping that change. This is the effort that we are seeing of Jim Crow. Some of these folks would love to see us as second class citizens. Some of them in Congress right now of this Tea Party would love to see you and me hanging on a tree” (Galer 2016).

Carson made a speech to an Islamic group that resulted in criticism because he mentioned that “American public schools should be modeled on Islamic madrassas”(Hibbard 2012). He later went on to host another interview with reporter Mary Beth Schneider of The Indianapolis Star. In the interview he mentioned that his words were “taking out of context.” The same day, he issued a press release mentioning that no “…particular faith should be the foundation of our public schools…” (Hibbard 2012)

Recently Rep. André Carson received a death threat at his Washington D.C. office after he “criticized Donald Trump over his proposed Muslim ban. Carson, who is one of two Muslim lawmakers in Congress, dismissed Trump’s comments as “asinine”(Shan 2015).

Carson is a rising member of House leadership. He serves as a Senior Whip for the House Democratic Caucus, sits on the powerful Democratic Steering and Policy Committee, and is a member of the Congressional Black Caucus’ Executive Leadership Team. “ (Carson 2016) These positions allow for him to “fight for Indiana’s 7th Congressional District at the highest levels of congressional leadership”(Carson 2016). Congressman Carson is a proud Indianapolis native, having grown up on the city’s east side. He is married to Mariama Shaheed, and is also a proud father of a ten-year-old old girl, Salimah.

Keith Ellison: First Muslim to serve in the U.S. Congress

Keith Ellison, the first person of color from Minnesota to be elected as a representative, was born and raised in Detroit, Michigan as a Roman Catholic. However, when he attended college in Minnesota he converted to Islam. After college he was a lawyer and radio broadcaster for public affairs.

In 2006, Ellison was elected to congress from Minnesota as a member of the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party. His ceremonial oath made national news, because he was sworn in with a Quran that belonged to Thomas Jefferson. There was much controversy about him not swearing in with a Bible like most do. Yet to his surprise there were some fellow representatives that actually approved of him using a book of his choice and even admitted to using different standards of books when they too were sworn in.

Since he’s been in office, Ellison has been called on many times to speak upon his faith. We talked a lot in class recently about the burden of representation and this is an example of that. There have been numerous occasions where Ellison has been asked to speak on behalf of topics that he is in no way associated with but just the fact that he is Muslim he is looked at to speak upon the matters.

Throughout his time in office, Ellison has also been viewed as a reliably liberal Democratic vote and has campaigned on his opposition to the Iraq War, his support for universal health care, and his vocal opposition of voter ID laws. But he’s also been accused of having anti-Semantic views that correlate with Louis Farrakhan, who is the leader of the Nation of Islam. They even tied this accusation with old articles Ellison wrote back when he was in college and working for the “Million Man March” which is allegedly created by Farrakhan. He was also accused of being part of the Muslim Brotherhood but that was later disproved.

Keith Ellison isn’t as well known amongst Americans as you would expect considering the fact that he’s been in office for a decade now, though we might suspect all that is about to change. Recently Bernie Sanders made a statement about Ellison stating that “We must also do everything we can to elect Democrats in Congress in 2018, and to take back the White House in 2020. We need a Democratic National Committee led by a progressive who understands the dire need to listen to working families, not the political establishment or the billionaire class. That is why I support Keith Ellison to be the next Chair of the Democratic National Committee, and why I hope you’ll join me in advocating for him to lead the DNC.” There is also a petition going around to gain support for Ellison. I believe this statement would put a lot more eyes on Ellison and make him more susceptible to criticism and hate from Islamophobes, but it could also strengthen his support from the Democrats considering the fact that Bernie Sanders is the one pushing for him.

Ilhan Omar: First Elected Somali American Muslim Women in Office

Refugees and immigrants, particularly Somali refugees, have been a hot topic in the recent election. There is a high concentration of the Somali refugees in the Minnesota area. Ilhan Omar, a female former refugee who was born in Somali, spent four years living in a refugee camp in Kenya, before moving to the United States as a twelve-year old. She is also the first female Somali American to be elected to Minnesota state legislature. Many theories that we have discussed in class have come up in direct quotes from Ilhan Omar, and within the articles.

Ilhan Omar said “one of the biggest challenges was overcoming the narrative that if you are a minority running for office, you can only win a seat in a district that is demographically in your favor” (NBC News). Her primary candidate, Phyllis Kahn, essentially said that Ilhan Omar was a popular candidate because she’s very “attractive to the kind of, what we call the young, liberal, white guilt-trip people” (NBC News). This is a perfect example of “Islam-splaining.” Phyllis Kahn, and other people including some media sources, attributed Ilhan Omar’s success down to the fact that she was a female Muslim immigrant, not the fact that she is a highly successful politician with policies and ideas that people support. She said she believes “in the possibility that all of my identities and otherness would fade into the background, and that my voice as a strong progressive would emerge” (Huffington Post).

Through that last quote, Ilhan Omar also expresses the idea of intersectionality, and that is important because she is relatable to multiple groups of people. Her “identities” include being: female, American, black, a Muslim, a refugee, and an immigrant. She also covers, which makes her visibly Muslim. Ilhan Omar said that her success is not only for her, but for “every Somali, Muslim and minority, particularly the young girls in the Dadaab refugee camp where I lived before coming to the U.S.” (Learning English). This is especially important, because of the large number of Somali people living in Minnesota.

Ilhan Omar inspires everyone because she has overcome so much, and still preservers. She hopes to “make our democracy more vibrant, more inclusive, more accessible and transparent which is going to be useful for all of us” (Time). Obviously, this should be the goal throughout our entire government, because people need someone who they feel represents them in the government. People also need to feel that they have someone who is directly representing their best interests in office, and she is an inspiration to young children. In 2014, she was attacked and physically assaulted. She returned to work the very next day, and make sure the attack didn’t “silence” her, and that she was “stronger than they think (she) is” (Fusion). This is a direct quote from something Ilhan Omar wrote herself:“I think the idea of having someone like me run and possibly win allows other folks who are afraid to put themselves out there to take the leap, and to lean in, and to be the change that they want to see, and be a little braver in that process.”

Barack Obama’s support of the Muslim community

Some Americans like to think of our country as a nation of immigrants and a nation of religions, but repeatedly we have failed to live up to our ideals, banishing fellow citizens from the American family because of their ethnicities or religious commitments. During Obamas campaign he was falsely accused of practicing Islam because of his family’s history with the religion and growing up in Indonesia during his youth years, in which he was heavily surrounded by people of the Muslim faith. Also his name, specifically middle name, “Hussein” which is commonly found in the Muslim community, generated allegations of Obama secretly practicing Islam which caused threatening views to others on Obama’s loyalty to this country. During his campaign he was attacked by many political opponents including Donald Trump. Trump questioned Obama’s commitment to America and even stated in 2012 “I don’t know if he loves America.” He encouraged his supporters to believe such claims, as they thought Obama was secretly harboring faith in Islam.

According to a CNN/ORC poll it was found that 54% of Trump supporters believed Obama was a Muslim. Among Republicans nationwide, the poll showed, 43% of Republicans thought Obama was a Muslim, as did 29% of Americans as a whole. Questions about Obama’s commitment to the country and faith led Obama to have to prove his “Americanness” and disassociating himself from the perceived negative notion against the Muslim community. But despite people’s accusations against Obama, he openly embraced being raised in different cultural places around the world. He discussed growing up in Muslim communities and how his childhood influenced his future attitudes towards America.

During Obama’s presidency he frequently defended the Muslim American community. Obama publicly showed his support and gratefulness to Muslim Americans contributions to our nation. Earlier this year he visited a mosque in Baltimore to rebut “inexcusable political rhetoric against Muslim-Americans” from Republican presidential candidates. During his visit he described Muslims as essential to the fabric of America, while attempting to reconstruct what he said was a warped image of Islam. “Let me say as clearly as I can as president of the United States: you fit right here,” Obama told the audience at the Islamic Society of Baltimore, a 47-year-old mosque with thousands of attendees. “You’re right where you belong. You are part of America too. You’re not Muslim or American. You’re Muslim and American.” He discussed in his speech the long history of Muslims in America dating back to the colonial times when Thomas Jefferson was threatened by people accusations of his involvement within the religion.

Obama has also demanded more positive representation in the media of Muslims in America. “We have to … lift up the contributions of the Muslim-American community not when there’s a problem, but all the time. Our television shows should have some Muslim characters that are unrelated to national security. It’s not that hard to do,” Obama said. Despite the negative repercussions that Barack Obama faced involving the Muslim faith, his acknowledgment of their contributions as Americans still remained. He challenged all Americans to be a part of a single community that appreciates one another’s differences while preserving the things that are essential to our identities. His message emphasized value and respect for the Muslim community in America which at this time in the history of our nation is something that is greatly needed.

Conclusion

All of these people deal with Islamaphobia while running for office. If you google “Muslims in the US government” the second page that pops up is “The Muslim Brotherhood Has Taken Over The White House.” Ilhan Omar was attacked and beaten. Obama, who is not even Muslim, faced criticism because of his background and his skin color. Obviously, this is very problematic, especially in a country that preaches separation of church and state. There’s still a long way to go, but there is good news though: there are now more and more Muslims in our government, giving us greater diversity and representation at both the national and state levels.

Further reading:

“Andre Carson – Discover the Networks.” Andre Carson – Discover the Networks. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2016.

Carson, Andre. “Biography.” Congressman Andre Carson. N.p., 2016. Web. 13 Nov. 2016.

Galer, Sara. “Andre Carson Responds to Tea Party Controversy.” 13 WTHR Indianapolis. N.p., 2016. Web. 13 Nov. 2016.

Garsd, Jasmine. “Rep. André Carson To Become First Muslim On House Committee On Intelligence.” NPR. NPR, n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2016.

Hibbard, Laura (July 6, 2012). “André Carson, Indiana Congressman, Says U.S. Public Schools Should Be Modeled After Islamic Schools, (VIDEO) (UPDATE)”. The Huffington Post. Huffingtonpost.com.

King, Mason (December 22, 2010). “Leading Questions: Carson talks Congress, whips, soft rock”. Indianapolis Business Journal. Ibj.com.

Shan, Janet. “Rep. André Carson Gets Death Threat After Trump Criticism.” Hinterland Gazette. N.p., 08 Dec. 2015. Web. 14 Nov. 2016.